Nalanda West Brings Tibetan Thangka Painting Master, to Teach and Create in Seattle

Written by: Jamyang Dorjee

Tibetan thangka painter R.D. Salga is known for his precise hand work, and for his adherence to the rigorous structure of the sacred art form.

Photos by: Nalanda faculty, Dolkar Nhangkar, Steve Wilhelm

Photos by: Nalanda faculty, Dolkar Nhangkar, Steve Wilhelm

Renowned Tibetan painter R.D. Salga has arrived to teach people the ancient tradition of creating Tibetan deities on cloth, called thangka painting, at Nalanda West in Seattle.

Nalanda, named after the former paramount Buddhist monastic university of ancient India, is bringing this similarly ancient thangka painting tradition to the Pacific Northwest.

In October Nalanda West and Salga opened his studios to the public, an opportunity for people to meet the artist and to see some of his work.

A display of some of Thangka painter Salga’s work in the studio at Nalanda West.

It was here in his new studio, in a small house behind Nalanda West, that I met Salga. His diminutive stature and quiet expression belie his encyclopedic knowledge of the sacred art of Tibetan thangka painting. His presence is so impressive I was moved to address him as “Salga la,” a Tibetan honorific of respect and veneration.

Salga, in this case Salga la, will over three years teach about the role of thangka painting in Tibetan Buddhism. He will share the art form’s history, purpose and symbolism, as well as teaching people how to draw and paint thangkas.

Thangka paintings are Tibetan Buddhist scroll paintings, often depicting Buddhas, Buddhist deities or mandalas. This type of religious art adorns the walls of many Tibetan monasteries and Tibetan Buddhist homes.

Thangka paintings serve as aids to teaching and practice, as each detail portrayed has deep meaning and refers to part of the Buddhist philosophy.

For example, to do Tara puja meditation it is important the practitioner know what the goddess Tara looks like, to be able to visualize Tara. The practitioner usually begins by looking at an image of Tara on a thangka. Practitioners similarly use thangkas to visualize other deities and important figures including Chenrezig, Guru Rinpoche or Milarepa.

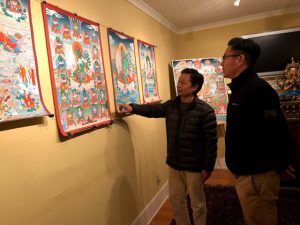

Painter Salga explaining the meaning of some of the detailed art in a Thangka painting to reporter Jamyang Dorjee.

Founded by Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche in 2004, Seattle’s Nalanda West offers programs and events inspired by fields of knowledge originally taught at the ancient Nalanda University, which thrived in India between the 5th and 13th centuries. The Seattle event center is mostly volunteer-run by Nalandabodhi, a Buddhist community under the direction of Ponlop Rinpoche.

“It was Rinpoche’s wish and vision, so that the Karma Gardri tradition is not lost and continues to live, that I come to Nalanda and teach it in the West,” said Salga, referring to the school of thangka painting he teaches.

Two main schools of painting dominate Tibetan thangka painting: The Menri style and the lesser-known Karma Gadri style. Salga was trained in the Karma Gadri school.

“The last time I was here…I spent about three weeks…did a small presentation on the Karma Gadri school of painting and the relevance of thangkas to Tibetan Buddhism.” Salga said. “Rinpoche spoke about the urgency and importance of saving the tradition, and talked about myself coming back again and staying a little longer the next time to teach.”

November visitors at the grand opening of Salga’s studio, admiring the paintings.

Few Buddhist centers anywhere in the world can boast of a thangka art class offering. The thangkas hanging at Nalanda West have been painted by master Salga. Patrons will have the opportunity to see his work, observe him in action, attend his classes, and learn from his workshops. Nalanda West hopes to offer different levels of classes, including higher levels if there is enough interest and participation.

“Salga la is indeed a wealth of knowledge and one of the few remaining keepers of the Karma Gadri school. We’re hoping we’ll receive some feedback from this story that will guide what path we take in regards to exploring this rare and valuable opportunity here at Nalanda,” said Damayonti Sengupta, general manager at Nalanda West.

Salga’s early years of training in Buddhism, and in thangka painting, came from his association with Rumtek Monastery, and from growing up in the nearby city of Gangtok, capital of Sikkim.

Perched high on a Himalayan hilltop, the impressive Rumtek is the seat of the Karmapa. The latter is the head of the Karma Kagyu order of Tibetan Buddhism, and thus Tibet’s second-highest lama only after the Dalai Lama.

Salga’s rigorous training came from the esteemed Tashi Gyamtso, who was one of the most famous and accomplished artists from the Karma Kagyu lineage. Gyamtso came from Tibet with the 16th Karmapa.

Salga La giving a brief tour of his art work and studio to reporter Dorjee.

It is Tashi Gyamtso’s work that adorns the hallowed walls of Rumtek Monastery. Tashi Gyamtso died in 1980. Many thangkas painted by Salga also are featured in and around Rumtek.

Thangka painting is a centuries-old tradition kept alive mostly by the Tibetan government in exile, through apprenticeships and training programs in Dharamsala, India.

“While there are efforts to keep the tradition alive,” Salga said, “The challenge often is finding accomplished and knowledgeable teachers.”

Once a rather comfortable and respectful skill in Tibet, thangka painting no longer holds enough value and economic benefits to attract others to the trade.

One of the reasons for this decline is the years of serious study and practice required to master the art. Unlike most art thangka painting is not a product of an artist’s imagination, but is rather a carefully executed production based on a series of blueprint drawings with specific guidelines that must be diligently adhered to. It is a labor of worship that takes a really, really long time to perfect.

A contemplative Salga.

The intricate and detailed work required requires serious discipline, focus and concentration. Each deity is based on geometric measurements that are accurate, researched, and written in ancient manuscripts. This measurement and accuracy carry great symbolic importance, as do the colors, the position of the body and hands, and any instruments in the deity’s hands.

China’s invasion of Tibet in the 1950s, and the subsequent destruction of a lot of old Tibetan traditions and monasteries, makes it even more important to keep this beautiful and ancient thangka-painting tradition alive.

“This is part of our cultural heritage, and losing that art will be losing part of our history,” said Jampa Jorkhang, president of the Tibetan Association of Washington.

When asked about his own vision, Salga said, “I’ve been drawing thangkas for years now so my hope is that I be able to pass down this skill to others.”

“The encouraging thing here in the West is that there are definitely people here who are interested in learning the art,” he said. “They are smart and eager to learn so they seem to pick up things quicker.”

Salga hopes that at the very least, people understand what thangkas are about and will get interested in them and want to learn the art.

Nalanda Group from left to right: Fitri Junoes, Julia Linderova, Salga, Damayonti Sengupta, Stephanie Johnston.

“A thangka painting is not simply a decoration or a creation of beauty, but a religious object and a medium for expressing Buddhist ideals, so that the practitioner can reflect and meditate,” he said. “Even to my students in Nepal, I tell them that it is important to have the right mindset and the correct motivation when drawing a thangka. The better the effort and purer the motivation, the more precious the thangka.”

But he adds that he understands that economic pressures, and the need to survive, mean that many feel they can’t continue dedicating themselves to the art.

When he first started learning many years ago as a child he was part of a group of 40 monks, Salga said. But slowly through the years almost all of them had dropped off and given up, to follow other more lucrative business opportunities. Now just he, and another person who paints occasionally, still carry the torch from the original 40.

Not all thangkas are painted. In Tibet some religious ceremonies and festivals are based on the unveiling of giant hand-woven cloth thangkas. These woven thangkas are often more than 150 feet tall and about feet wide, and are unfurled down walls of monasteries, cliffs, or steep mountain sides.

To understand the depth of an accomplished thangka artist like Salga la, ponder this: The next time you look at a thangka, no matter how intricate and exquisite, chances are the entire creation was painted from memory. Another point is that a thangka painter never signs a thangka painting. This would be considered an act of desecration, not true to the Buddhist principles of non-attachment and letting go of ego.

If you’re interested in contacting Salga to offer a guest lecture, please email at info@nalandawest.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment