Seattle Tibetans Unified Through Covid-19

Written by: Jamyang Dorjee

Sonam Nyatsatsang sings a group song with board members at the Tibetan community New Year’s party at Northgate College.

Photos: Kurt Smith, Tibetan Association of Washington

When the 250 members of Seattle’s Tibetan community gathered Feb. 29 for their annual Tibetan New Year’s party called Losar, the phrase “social distancing” was virtually unknown.

Face masks were for Halloween, and washing hands was mostly a morning hygiene ritual accompanied by brushing one’s teeth.

Tibetan community members gathered at Sakya Monastery on the first day of Losar, the Tibetan New Year.

Losar is the biggest occasion on the Tibetan calendar, often celebrated for two weeks to a month. Organized by the Tibetan Association of Washington, the Seattle holiday had started earlier that week with community prayers at Sakya Monastery in Seattle, with Tibetans dressed in fine traditional garments called chubas. By Feb. 29 they were moving on to a rented facility at NorthGate College, also in Seattle.

But behind the scenes awareness of the developing COVID-19 epidemic in China was rapidly growing, including among Seattle-area Tibetan doctors closely monitoring developments in China.

Dr. Sonam Nyatsatsang, a physician at Swedish Medical Center and a Tibetan Association of Washington board member, was in charge of drinks for the party. But in the back of his mind he was weighing bringing up Covid-19 at the celebration. Wanting to be sensitive to the celebratory mood, he was having second thoughts about introducing topics like disease and basic hygiene.

As the pandemic developed over subsequent months, Tenzin Topchen, a Boeing engineer and newly elected president of the Tibetan Association of Washington, realized he and his team of youthful board members had a challenge on their hands.

Chemi Chekal and her children preparing to offer respects before the altar at Sakya Monastery for Losar.

Deep cultural and ethnic connections within the Tibetan community meant Topchen and his team had special responsibilities for the welfare of more than 350 Tibetan community members. Community members are vulnerable in many ways, with many of them working in the service industry, others in health care. The community also includes a group of elders.

Topchen says overall it hadn’t been too bad, and impacts on Tibetan people have been mostly financial.

He knows of several families whose members have been furloughed or laid off from their jobs. Some hit financially were Uber and Lyfte drivers who lost fares, while others had to close down shops.

The small community of Tibetan elders has had to make many adjustments. Tibetans typically live in close-knit, multi-generational home structures, where older retired people take care of younger grandchildren while the children’s parents go off to work. The working parents in turn take care of their own retired fathers and mothers.

But social distancing guidance from state health experts, due to the increased vulnerability to the virus of the older generation, made it hard for the generations to take care of each other. Suddenly they were faced with hidden threats in the simplest acts of family closeness, hugs, shared meals, or time spent together praying as a family.

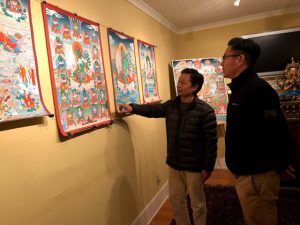

Khenpo Jampa Rinpoche of Sakya Monastery praying, in a screenshot of the monthly Tibetan community prayer session, now on Zoom.

The association has focused on improving awareness and education through regular emails and social media posts to the community, sharing guidance about the virus from local health government and public health agencies.

In May board members spent time calling around and checking with Tibetan community members to see if there were Tibetan elders who needed help with basic tasks like grocery shopping. They didn’t find any takers, which Topchen attributes to the care that elders already were receiving from their close multi-generational families.

As another source of help the Tibetan Association received a $1,200 grant, through a partnership with the South Asian community organization UTSAV, for distributing food to families impacted by the pandemic.

Topchen is particularly pleased with a weekly YouTube series about COVID-19 that his team created with Nyatsatsang, the physician. The videos included questions from the Tibetan community, with Nyatsatsang answering in Tibetan.

Khenpo Jampa Rinpoche turns a prayer wheel, also on Zoom.

The videos were shared on the association’s Facebook page, and Topchen saw good engagement and received positive feedback. The videos also were shared with larger Tibetan communities worldwide including in New York City, where Tibetans were hit quite hard due to their sizeable older population.

As an active community member of the association, Nyatsatsang was as usual glad for opportunities to help, although this also increased his own risk for the disease.

Nyatsatsang’s world went into overdrive after the virus outbreak. In addition to his day job at Swedish he volunteered with the Tibetan Allopathic Physicians Network, The Central Tibetan Administration Department of Health, and others. He was happy and eager to help, as always.

But unknown to him at the time, the long hours were taking a toll on his body. About a month into the pandemic Nyatsatsang fell ill. He felt chills at work and was unusually tired on a Friday evening while driving home. The next Monday, after recovering over the weekend, he felt feverish with a headache and promptly drove to the Swedish Medical Center emergency room.

Tenzin Topchen, president of Tibetan Association of Washington, with his team of newly-elected board members.

Aware of the negative social stigma about disease in Asian communities, Nyatsatsang waited until May 10 to tell family and friends he had contracted COVID-19 and was on the path to recovery. By the end of the month he had recovered enough to go for a short hike with his family.

Meanwhile the association has been responding flexibly to new needs created by the virus, for instance by re-starting on Zoom Tibetan community prayer sessions, which previously were done in person at Sakya Monastery. Weekly Tibetan language and culture lessons for the community’s children also have been moved to Zoom.

Looking farther afield, the community has been able to watch online video teachings by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, live from his residence in Dharamsala, India.

Despite the difficulties, Topchen feels the community has taken the pandemic in stride. “Our Buddhist outlook and attitude towards the impermanence of things gives us I think a slight psychological advantage of knowing that this too shall pass,” Topchen said. “As refugees and immigrants, our community members have seen a lot and been through more. This changes how one views life and how we live it.

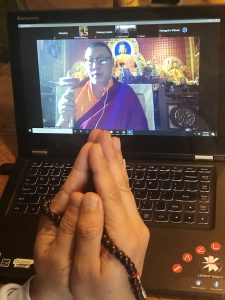

A community member participating in a monthly prayer session, on Zoom.

“There is an acceptance that life throws challenges at you, and you learn to make adjustments to be able to move on,” he said. “You don’t just take things for granted, even life.”

Topchen said his Buddhist upbringing has taught him to have a less individualistic mindset, and therefore to think about the collective and the greater good.

“This attitude of thinking beyond yourself, that it’s not just me and that everyone else around the world is dealing with the same, makes it easier to understand,” he said. “The alternative just puts more pressure on yourself and leads to more stress.”

He adds that losing simple things like going out to eat and hanging out with friends…makes you truly appreciate all the little things in life. He said the losses include “Talking to friends and family without observing social distancing, things we take for granted and now miss.”

Nyatsatsang said he remains glad about his opportunity to alleviate human suffering, and is happy he could respond.

“I strongly believe in Tonglen,” Nyatsatsang said, referring to the Tibetan Buddhist practice of breathing in the suffering and pain of others, while breathing back healing.

Cultivating awareness while going through his own COVID-19 suffering, by absorbing the suffering of others and transforming that to generate compassion, gave him peace of mind, Nyatsatsang said. These are mindful words from a medical doctor.

Jamyang Dorjee is a Tibetan Buddhist living in Bothell, Washington, with his wife and two children. He is a former president and board member of the Tibetan Association of Washington. He also serves on the board of Leadership Snohomish County, and writes regularly for Northwest Dharma News.